Edited by Maggie Rosenau

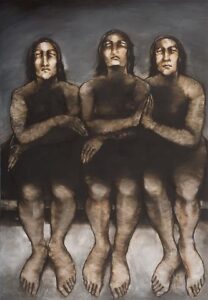

Artwork: Rima Salamoun

We are all ruled by our fates. The difference between people is whether one accepts it or not. Humbly accepting one’s fate means being ready for anything bad or good that might come. What causes us rage is when, no matter how we try, we cannot accept our fates, our living dignity. Because we do not allow ourselves to accept humiliation, or allow someone to make less of us. Thus, pride becomes a reason for death.

– How did he die?

– His pride killed him!

The underground life among people and diseases—especially in our ward Nr.12—made us long for newcomers every day. However, not for any newcomers. We wished for someone who was rich and had a lot of Syrian pounds at the time of their arrest. Like—someone who just got his salary a half an hour before he was arrested on his way home.

I remember the first moments after entering the prison dormitory. When the guards closed the door after letting us in, most of the prisoners started asking us “new prisoners” the same question: How much money do you have? I believe I answered that question more than twenty times that day.

There was a 65 year old man who entered the dormitory with me. As I remember, he had an Emirates asylum and was working in Dubai. He was visiting his family in Homs city and on his way back to Damascus airport, he was arrested for a reason unknown to anyone except those who detained him. When people asked how much money he had, he replied, “I have ten thousand Syrian pounds and about seven hundred dollars.” When people heard that, they cheered and each tried to convince him to “Join my group!” or “Join our group!”

Early on, I didn’t understand all that questioning about other people’s money. And when I noticed people trying to bring older men into their groups while ignoring those of us with little money, I decided the whole situation was about greed and making deals.

A bit of money allows prisoners to buy things like skin creme, cigarettes, salt and sugar, toothpaste, toothbrushes, soap, hair removal cream, and various sweet, bitter, and sour foods. Hearing about this for the first time made me consider. I did have four thousand Syrian pounds, and I could offer to buy items once or twice. But then I was informed that prisoners had to order double what they desired, because half would go to the prison guards. So, if I wanted a toothbrush, I best order two. In the end, four thousand Syrian pounds isn’t really a luxury and would not offer me much.

One of the prisoners who looked around my age came up to me and said, “Hey, my name is Khaled! How long have you been detained?

Me: Anas is my name, and I have been detained for five days.

Khaled: They arrested me four months ago on the charge that I defected from the army and joined the terrorist groups “Free Army“. And you? What reason are you here for?

Me: They wrote a report accusing me of possessing a weapon and a Thuraya communication device. They really have nothing against me though—they want me to confess to the false claim and tell them where I hid these things. It seems like this is all orchestrated for their entertainment or to make me say something else. I don’t know exactly. So you are a soldier?

Khaled: I used to be! When I still believed that the main role of the army was to protect people, not to kill them. Have you joined a group yet?

Me: No, not yet. They are busy selecting the richest first.

Khaled: Do you want to join my group?

Me: I would love to!

Khaled: Great! Welcome to the group. May I ask how much money you have?

Me: I have four thousand lira!

Khaled: That’s good, better than nothing.

Back then, Khaled was twenty years old, one year younger than I was, at the time. I remember when he introduced me to the group members, speaking with full confidence, like he was in charge of taking care of the group’s business. I noticed later, as he received the group’s share of food, that he divided everything equally among members of his group.

Khaled was someone who liked to talk about his past and the stories of his youth. He talked about his adventures as a teenager with girls and the problems he had because of them.

Khaled also loved to talk about his family, especially his little sister—how much he loved her and how he was willing to do anything to make her happy after his father passed away. He always reminded me how close they were, how she was his safe place to keep his secrets, and how he was everything to her.

If he wanted to hear someone’s story, he would listen carefully and ask about the smallest details. Kahled was a quiet person who sat with his back against the wall. Most of the time we saw him silently fixing his gaze on the corner of the ceiling of the room. He was also quick to anger and ready to fight over any small problem if someone upset him with a single word.

As a detained soldier, he was in a difficult situation. I knew that soldiers who defected from the government army are interrogated in the security departments for several months, then transferred to the military court in Damascus, where they are often sentenced to be executed on the spot. There are various ways this takes place. The soldier might be transferred to the Saydnaya mountain prison in Damascus, or they might be taken to isolated mass graves, executed, and buried there.

Sometimes Khaled spoke about the future that awaited him—sometimes in a negative way, how he will die for nothing. Other times he spoke positively, explaining that death is much better than what we are living and experiencing now. I don’t know how positive that sounds now, but for me at the time, it was positive and I agreed with him. I think that way of thinking prepared us for our end—while we were still smiling.

In the first three months, we developed a close friendship and cared for each other. I remember sitting in front of him, face to face, sometimes even forehead to forehead, when we had to keep talking in whispers so that no one would send us out for punishment for making noise.

Imagine what a hundred people locked in a small room talking in low voices sounds like.

For us as prisoners, it wasn’t a big deal. It didn’t bother us. We needed to talk, to express our needs, to tell our heritage, our stories, or what was left of them. But for the guards standing outside in the hallway, hearing the sounds of one thousand prisoners spread across thirteen cells, was rather annoying, which sometimes made them even more brutal.

So Khaled and I spoke most of the time together in whispers, sharing what we could tell, what we could remember, even the silliest stories and secrets. When it seemed we had nothing left to tell, we continued to sit next to each other, mostly in silence.

For a while, Khaled became calm and speechless, like anyone who has spent over six months in such a prison, but that didn’t last long either. One day in February, there was a mass poisoning throughout the prison, causing diarrhea. We believed that someone had added poison or medication to the water. Every detainee was affected, and we spent two to three days trying not to shit ourselves while waiting in line for the toilets.

The problem, though, was that two out of thirteen wards didn’t have a toilet booth, so the guards had to open the doors for prisoners in those dormitories and let them go to the bathroom elsewhere. The guards would beat the prisoners upon entering the bathroom, then give them until the count of 20 to finish. That added stress made those of us with toilets in our dormitories very thankful. But after a day, the guards decided to split the roughly 200 detainees in the toilet-free wards among the remaining eleven wards. We heard them discussing how to prepare a place for at least twenty new prisoners for station number thirteen and station number nine. I don’t know what they meant by “prepare,” but it was more like they were stacking us on top of each other. When the next morning dawned and the station doors were opened, we were ordered to greet the new arrivals and give them a seat and priority to enter the toilet as soon as possible, which we did!

When the new prisoners had finished relieving themselves, Abu Ibrahim ordered them back in line to be divided into groups. Khaled and I counted twenty-two new prisoners ourselves, so we totalled about 120 prisoners in Station No. 12 that day and the following week. When the new arrivals got back in line, Khaled noticed a young man who seemed to be about our age, so he nodded to me, pointed at him, and said:

Khaled: Look at that fellow! He seems really nice, let’s talk to him and add him to our group!

When I winked at him to show my approval, he quickly jumped up from his spot and went to him.

Kahled: What is your name?

Aamer: Aamer!

Khaled: (gesturing toward us) Do you want to join us in the group?

Aamer: Sure! without hesitation!

Khaled: Ey Abu Ibrahim!! We have accepted Aamer in our group!

Abu Ibrahim: How much money do you have, Aamer?

Aamer: Nothing, actually!

Abu Khaled: Then yeah sure, you can join his group!

Our group received Aamer and another man in his forties whose name I don’t remember. We made a small place for Aamer to sit with us so we could talk and hear new stories in our small circle. We started with the basic questions: When were you arrested? Where did they arrest you? And for what reason are you here? To ask a prisoner how long he has been imprisoned is to ask about his pain, his struggle, to know how long he has been in exile.

Aamer: This is already my second arrest within a year. For the first one, I was caught distributing street posters with obituaries for Bashar al-Aassad. We were supposed to be a team of four for this mission: one person to put posters on the walls, two people to keep a lookout, and a car driver who would drive us away in case we were caught or noticed. Just before the mission started, one of the lookouts couldn’t make it, so the driver helped me put up posters. Meanwhile, the street cleaner saw us and called the security police. It wasn’t long before I felt a gun pointed at my back and a voice ordering me to throw the posters and not think about running away. They arrested me and the driver, detaining us for eleven days. We were lucky that there was a presidential pardon back then for new political prisoners, which ended up including us both.

After my first arrest, I was serious about expressing my political views or opinion in public, especially at my university. I thought I would be aware and careful about who I spoke to or who listened to what I said, but that didn’t go as planned. A member of the student union, whom I don’t know personally, betrayed me and wrote a report accusing me of having liberal views and claiming that I was working against the government. One day, I was walking to the university gate with my ex-girlfriend and this guy was standing there waiting for me to come in. When I walked through the gate, he stopped me and said to the soldier next to him: this is the one we are looking for. They took me to the soldier’s room near the gate as quickly as possible, and there they examined my belongings and my phone. First, they found a video of the destruction of the Qudseya area in Damascus. I tried to escape this by saying that I have such a video on my phone just to show my friend what the terrorists did to his hometown. But then they found revolutionary songs, putting me in a situation. They beat me, tied me up, then brought me here.

At the beginning of the examinations, they tortured me and tried to find out why I made the video and why I had the songs on my phone. I didn’t say anything serious that condemned me, and now I have been here for almost three months. Before the poisoning happened, I was in Ward No. 9 and Ward No. 2. Now I am here.

We found a good friend in Aamer. With him, our life was easier and more colorful. Even our struggles were divided by three. We shared food, we shared our places so that the most tired of us could sleep a few hours, and we took beatings for the other older or younger men. We fasted almost every day, gathering our daily food until sundown so that we could have a nice and filling meal at the end of the day.

One April night, when most were asleep, we were considering fasting for the day. But our problem was that we were already starving without much food, and it would be really hard to fast for the whole day. In such cases, the only option is to find someone who often keeps food for the next day. There were some who didn’t eat much, or who had money and extra food from the prison market. Or the new arrivals who lost their appetite in the first week and didn’t eat any of their share. Maybe they gave it to someone they like.

We started asking people who were awake if they could share something to eat for our Suhur, explaining that we wanted to fast that day and needed something to help us along. Of course, we asked the affluent, who always had something to eat, and it was very successful. We were able to collect two pieces of pita bread, two pieces of boiled potatoes, an egg, some yogurt and a tomato. It was a great happiness to see all that merged together in a small bowl. We ate joyfully. It was like a feast for three people at the end of the night. After that feast, as I recall, I washed and stood under the window to pray. Preparing to pray, I glanced at the only skyline we had access to and saw that dawn had already arrived—the sun had risen a long time ago. Quietly, I went to Aamer and Khaled to tell them what I had seen. We started laughing out loud, then Khaled warned that people were asking why we were laughing.

Khaled: Keep quiet, don’t tell anyone that the sun has already risen!

Aamer: Right, we have to keep fasting, at least we can’t eat anything in front of anyone during the day!

Me: yes, or else they will demand that we give them their food back from our shares for today!

We agreed to pretend to fast in front of the others. It was funny and also exhausting to watch the others eat while acting as if we were fasting. It was a sort of victory in such a place—being able to get a free meal for three people. That was the only day in Ward No. 12 where I laughed a lot and enjoyed spending time with new friends.

There are too many memories to preserve and too many stories to tell, but even stories must come to an end. This is also how it goes for Khaled. After six months in prison, he went back to his deep silence—aware that despite all the chaos here, he wanted to be alone in his own place where he could lean his back against the wall atop a pile of things that were put together to form a small chair. Later, he became even more aggressive toward people who annoyed him. Aamer and I spent most of our time talking and keeping an eye on Khaled while he was deep in his thoughts, not caring what was going on around him as long as no one was interrupting his thinking. It was so hard for us to see him drift away from us, to be next to a friend that we considered a brother, while he was locked away and distant in his mind.

A few days later, they pulled me into some kind of investigation. This developed into a raid on my home to arrest my brother and collect data. The goal was to collect information that would condemn me and keep me in prison for a longer term than the original accusations would allow (those accusations consisted of three demonstrations and a riot). After the raid, guards called me again for what turned out to be my last investigation in the prison. And I was waiting for this interrogation after I saw so many things taken from my home during the raid. I saw them walking out of my apartment holding two desktop PCs, one was mine, the other was new, and I had no idea whose PC it was. I was mostly afraid of this PC, I trusted that my PC was clean and did not contain any revolutionary pictures, songs, or other documents that could be used to incriminate me. This new red PC that I had never seen before kept me in a state of fear as I waited to be called in for the next interrogation.

When my number was called, I answered and left the dormitory as quickly as possible. The jailer ordered me to follow him up the stairs. He took me to the second floor. When we arrived, two guards were standing in front of an open door that looked like an office. One of them was my investigator—the same one who had questioned me from the beginning. He was standing and waiting for me with a wooden stick in his hand used to beat prisoners. When I came closer to him, he pointed the rod at my face and said:

Investigator: Give me the password for the PC!

Me: Sir, when they took me to my home, I saw two PCs taken out of the house—the black one is mine and has no password to access the desktop. The other one is red!

Investigator: That’s exactly what I need! I want the password for this red PC!

Me: Sir, I have never seen this PC before. It is new, I swear! The first time I saw this PC was when they took it from my apartment. I assume my father or brother bought it after I was arrested and kept here, and that was almost five months ago now.

Investigator (hits me): Liar!

He started beating me with his rod. He then ordered the guard who brought me up to cover my eyes and take me to a room where they could beat me without causing more noise on the second floor. The guard covered my eyes and kicked me into an open chamber that smelled of blood and rotting flesh. He continued beating me while I was on the floor until the investigator came in and he said:

Investigator: What is the password?

Me: I swear I don’t know, I’ve never seen this PC before, sir!

Investigator: Here’s a paper and a pen, you have ten seconds to write down the password for me!

Me: But sir, I swear I don’t know….

Investigator: Try not to fill this paper with the password, then you’ll see what I’ll do with you!

I took the pen and the paper with shaking hands and thought of every possible password my father or brother could have chosen for a pc. i wrote down all the numbers and letters that came into my head and gave them to him as i said:

Me: Sir, I’m not sure if the password is one of these!

Investigator: I will check, then you will know if any are correct or not!

As he left the torture chamber, I scrambled to come up with additional password options like phone numbers, birthdates, my brother’s ex-girlfriend’s name, or even simple passwords like four times zero or 1 to 5 or up to 9. My mind was racing for a password to a device I had never seen before because there was a 99% chance the ones I had written down wouldn’t work. And sure enough, not five minutes had passed before he came back in, walked right up to me, and started swearing and beating me with the same rod. Handing me the paper again, he told me to write down the correct password. I took the pen and paper and started writing down every possible number or name that came to mind while insisting I had no idea and was writing anything and everything that was coming to mind. He took the paper and went to try them out. Meanwhile, the guard continued to beat me until the investigator returned with instructions to take me back to my ward. I don’t know if any of those passwords happened to work for him, but I preferred not to ask and just quietly left the chamber with the guard.

When I returned to ward No. 12, my adrenaline quickly went from very high to low—that precise moment when fear of being brutalized disappears and we feel safe again. I went to my seat near Khaled and Aamer and they asked me what happened and what the investigator wanted now. When I heard myself explaining what had happened upstairs, I started laughing out loud.

Me: I really wanted to say that I don’t know what they wanted from me, but they wanted a password for a PC that I don’t know anything about! They’ve been beating me for the last half hour for a password that I don’t have! They almost hanged me for that.

I didn’t know then what was happening behind the locked door of the ward. And I certainly did not know that I was at the end of a process that would get me out of there—that I was close to gaining my freedom back. What I still can’t forget is how lost in thought I was not knowing what else they wanted from me after I had already given them my confessions and signature.

Despite all our losses and noise in our minds, Aamer was the calmest of us. His composure in hard times gave me hope to escape this hell. On the other side of things, Khaled went back to isolating himself after the story of my latest interrogation. He became even more silent. His head full of noise and cries that, if mankind could have heard them, it would tremble from the severity of his suffering.

We are the voice of what we think, what we feel, what we say. We are slaves to our ideas because they are our ideas.

You are slave to what you feel, even if you want to change how you feel. Even if you reveal your true self and disclose questions—just feel me, hold what I am about to say…

I am hurt, so you have to feel my pain.

I am happy, so you have to feel pleasure.

These truths will not change, even if you keep quiet or make a prison for yourself.

If you were water, philosophy would not change that. Neither would prison—you would simply flow.

If you were a dream, time would not change this and neither would water.

You can become a gentle being or a wet, fleeting, uncatchable morning.

**************************************************************************

It is all in your mind. Wake UP my friend!